As I recall, the report I wrote on Billabong last year broke the 4,000 word barrier. I’m probably the only person who read the whole thing. But there was chaos and uncertainty last year and it seemed necessary to explain everything that was going on.

As of this year’s end at June 30, there’s still chaos and uncertainty, but the chaos is more positive in the sense that it’s self-generated as Billabong’s new management team restructures pretty much every function and activity in the company in pursuit of a more efficient and competitive organization. The uncertainty is around how quickly they can get it done and just what the impact will be.

Before we get started,

here’s the link to Billabong’s investor relations page. Under “Featured Report” you can view, from top to bottom, the financial report, the presentation CEO Neil Fiske used to explain the results, and the press release. I’d suggest ignoring the press release. A little further down under “Upcoming Events” is the link for the August 28 earnings presentation, where you can listen to CEO Fiske discuss the results.

My suggestion is that you go review Neil Fiske’s presentation. It’s the best summary of what’s going on.

Normally, this is where I’d leap into the income statement results. We’ll get to that. But because so much is going on, and so much change is happening I am, bluntly, less concerned about the income statement than I’d normally be. I’ll start by highlighting some things Billabong has to do well if the turnaround is going to work. All numbers are in Australian dollars.

Success Factors

Let’s head directly to the balance sheet. Last year at June 30, with issues of unhappy lenders and liquidity problems highlighted by a “Wow, am I glad I wasn’t the CFO” current ratio of 1.02, Billabong wasn’t likely to be a going concern without a restructuring. As we know, they got the restructuring done. At June 30, 2014, there’s an imminently manageable current ratio of 2.2. Receivables and inventories are down significantly (due to the sale of West49 and Dakine, closing of 41 stores, and writing down and liquidating some inventory) with total current assets reduced by 20.4% to $496 million. Cash is $145 million compared to $114 million a year ago.

Current liabilities are down 63% from $612 to $225 million. Non-current borrowings, however, are up from $6 to $212 million as a result of the restructuring. Overall, total liabilities are down 30%. Total liabilities to equity has improved from 2.27 to 1.90 times.

Even with the improvement in the balance sheet, CEO Fiske tell us that market and branding programs, as well as the new management team, will be funded from efficiencies and expense reductions in other areas. They don’t really have a choice. Billabong is financially out of the hospital, but not yet ready to run a balance sheet fueled triathlon.

Cash generated by operating activities was a negative $77 million compared to a positive $12 million in the previous year. Most of this, we’re told, was due to refinancing and restructuring costs.

Second, and maybe it should be first, let’s talk about the quality and potential of brands. Billabong is placing its bets on the Billabong, RVCA, and Element brands. Of the Billabong stable of brands, these are clearly the three that offer the volume and/or growth potential the company needs. That they’d focus on them is unsurprising (Billabong’s other brands are Kustom, Palmers, Honolua, Ecel, Tigerlily, Sector 9 and Von Zipper).

Neil Fiske’s predecessor,

Launa Inman, spent something like $1 million on consulting to find out what the brands stood for and where to position them. We never heard much about the results of that work. Let’s hope it’s given CEO Fiske some useful information.

These three brands already have a market position and stand for something with their existing customers. The challenge for older, established brands in our industry is to keep their existing customers as they age while also appealing to new ones. This is the time, when the public markets will be a bit patient if only because they recognize they have no choice, when Billabong can clean up its inventory and distribution even at the short term cost of some sales, and they are doing that. At the highest strategic level, every step the company is taking is about solidifying and building these brands.

Management is a big issue, and it sounds like there’s progress there. There’s a new executive leadership team in place, and below that level we’re told there have been 63 key hires or internal promotions. Some of the senior team has come on board within the last 100 days.

It speaks well of Neil Fiske and the company’s prospects that he’s been able to get so many apparently highly qualified executives on board so quickly. There are global heads in place for each of Billabong, RVCA, and Element.

You know that Surf Stitch and Swell were sold after June 30, with the deal to close shortly. Other owned brands are being evaluated for their potential. He didn’t quite come right out and say it, but it was pretty clear that brands not pulling their weight will be sold.

My guess is we’ll see some additional brands sold. It would be consistent with the “bigger, better, fewer” approach to its business Billabong has enunciated as well as its continuing, if lessened, financial constraints.

Next, they’ve got to fix North America. CEO Fiske was direct in describing the problems in North America. He noted that the corporate and leadership turnover hit the region hard and that the impact would be with the company a while longer. He further stated that it has suffered from a lack of good inventory management, poor buying decisions, and a historic tendency to overbuy inventory.

When we review the numbers, you’ll see the impact clearly.

Let’s not forget all the critical operational stuff that has the potential to generate many millions of dollars in incremental cash flow. SKUs are already down 20% with, I suspect, further reductions to come. They are rationalizing their supply chain and expect over some years to capture $20 to $30 million in incremental profit. Like most companies, they are working to get the right product to the right markets faster and are coordinating that effort with their marketing and merchandising.

What I just blithely said in two sentences is a monster project that touches every part of the company. It will be- it already is- messy, complex, and full of surprises. If it wasn’t I’d be worried they weren’t doing enough of the right things fast enough. Not to overdramatize, but Billabong is basically rebuilding itself for the modern world. It will take a while, and will really never be completely done because the market will keep changing. But it has to happen.

Yeah, maybe I did overdramatize.

By the Numbers

This is complicated. That’s because there’s been a lot going on over the last year. The on again, off again, finally closed deal costs, the restructuring costs, and the write downs made financial comparisons a bit difficult. Billabong has tried to help by providing a breakdown of all these costs and financial statements with them excluded.

I hate the way companies exclude so called extraordinary or nonrecurring items, because there seem to be some new ones every year. But in this case, the numbers are so big I mostly think it’s a good thing to do. I’m going to work almost exclusively from the statutory report. We’ll start with the numbers required to be reported, and then break out all the hopefully one-time items that Billabong calls “significant costs.”

As reported, revenue from continuing operations rose 1.6% from $1.107 to $1.125 billion. The gross profit margin slipped a bit from 51.1% to 50.6%, but that’s not surprising given the cleaning up going on. I’m glad it wasn’t more.

The loss before taxes and discontinued operations fell from $654 million to $167 million. But almost all that improvement was in the Other Expense category, which fell from $748 million to $167 million. Last year, remember, was the year of the huge noncash write downs for goodwill and brand value.

Interest expense, to nobody’s surprise, rose from $12.4 to $34.2 million “…driven primarily by the new financing arrangements…”

Believe it or not, income tax expense was $75 million, up from $30 million last year. Yes, I know- losing money but paying taxes seems odd. But lots of deals and lots of restructuring can make it happen. Feel free to read all the fine print about it you’d like.

After tax loss from discontinued operations was down to $30 million from $179 million last year. The discontinued operations include Dakine and West 49 which were sold during the year, and the interest in Nixon which was restructured. That leaves a bottom line loss of $240 million compared to $863 million in the prior year.

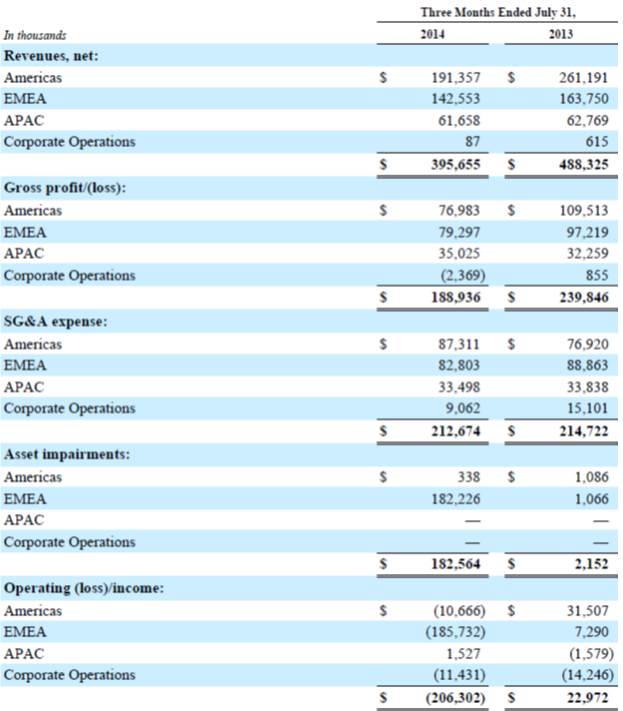

Okay, let the fun begin. Below are the segment revenues and EBITDAIs for both years as reported. These numbers include discontinued operations and the significant items.

Europe isn’t exactly a thing of beauty, but at least the loss declined some even as revenues fell. You can see the biggest problem by far is in the Americas. If you’re interested, revenue from discontinued operations was $238 million last year and $98 million in fiscal 2014. In his discussions of the Americas, CEO Fiske refers to Billabong’s forward orders growing and RVCA “reaccelerating.” About Element he says “…rebuilding underway.”

Now, here’s EBITDAIs by segment excluding first the significant items and then those items and discontinued operations.

You can see that the EBITDAI goes from a loss of $52.3 million as reported to a gain of $52.5 million. Take a moment to compare the third column in the first chart with the second column in the second chart.

They also provide the chart above in constant currency. But the results aren’t different enough for me to feel like I need to inflict it on you.

2014’s reported loss of $240 million becomes a net loss of only $14.4 million with all that stuff excluded. The 2013 loss of $863 million becomes a gain of $7.7 million. Those are pretty significant differences.

I want to say just a few words about what’s in those significant items. For those of you who really want the details, it’s all laid out starting on page 98 of the statutory financial report. I don’t think Billabong has to worry about its servers crashing as people flock to check it out.

Significant items from continuing operations totaled $116 million in 2014 compared to $669 million last year. The decline is mostly the result of the write off of goodwill, brands, and other intangibles falling from $440 million last year to $29 million this year.

You may remember my ranting from last year as I looked at these items. Some of them I can understand excluding, but in other cases the argument seems weak.

The poster child for ones I don’t think they should do this with is “Net realizable value shortfall expense on inventory realized.” They wrote off some bad inventory. It was “only”$14 million this year compared to $23 million last year. I know it was a different management team, and you really, really promise not to do it again, but I guarantee you will have some inventory write downs this year.

What bothers me is not that they do this- I think it can have value in representing the company- but the apparent discretion management has to decide how much of it they do. This is why I strive to pay the most attention to as reported numbers.

There are three things you should focus on as you evaluate Billabong going forward; the balance sheet, brand strength, and gross margin. The balance sheet will help you figure out if the company will have the financial strength to do what it needs to do. Brand strength is, at the end of the day, the one thing they can’t get along without. Improving gross margin will tell us that the operational changes they are making are having an impact.

I like the plan. Now all they have to do is do it.