It’s not usual that I’m happy to see a decline in year over year revenues during a quarter, but in the case of Quiksilver, I think I’ll make an exception. Their revenues for the quarter ended January 31 fell by 4.8% from $412 to $396 million. But at least some of that decline is from cleaning up distribution and I love that. In fact, I think it’s where Quiksilver needs to start.

As most of you know, their earlier financial problems led them to push brands for revenue in ways that weren’t good for those brands even if it was what the company had to do. To build their brands now, they have to exercise some caution with distribution.

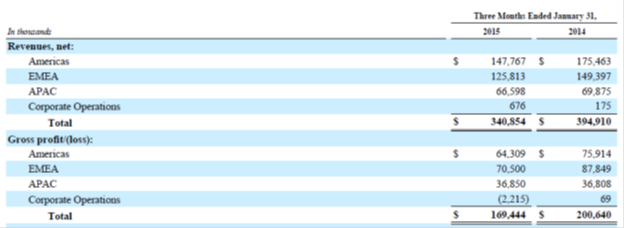

Here are their results by segment from the 10Q. EMEA is basically the European area and APAC is Asia and the Pacific.

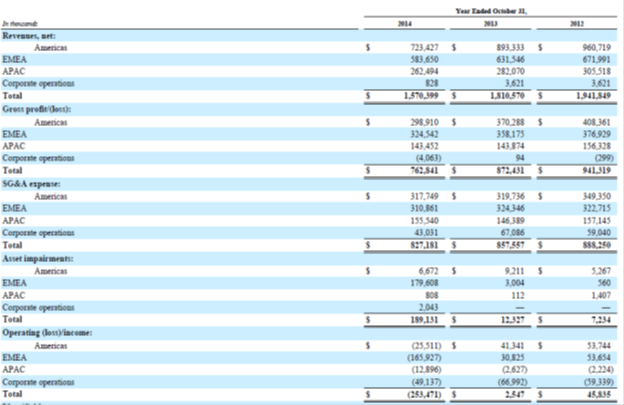

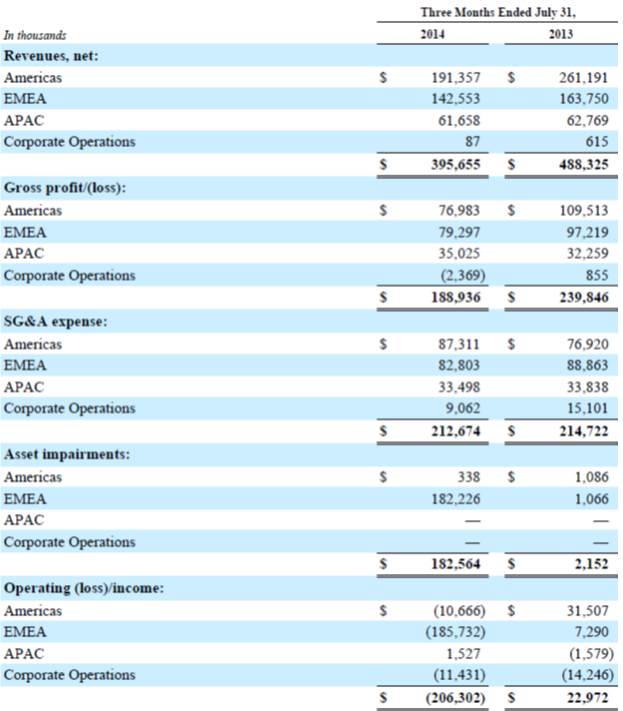

Here’s the operating income for each region:

You can see that revenue was down in each segment, but so was SG&A expense. In constant currency, revenue fell 2%. Below are the revenue numbers by brand as reported in the 10Q.

They only discuss the individual brands’ performance by region in constant currency. Quiksilver and DC revenues were off in the high single digit percentage in the Americas. Roxy was up by a similar amount. “The net revenue decrease in the Americas wholesale channel was focused within North America where net revenues decreased by a high single-digit percentage due primarily to three factors: 1) lower sales of DC brand products of approximately $6 million as a result of improved management of channel inventory to better align sell-in with sell-through; 2) a reduction of net revenues of approximately $2 million as a result of the discontinuation of the Quiksilver women’s product line in fiscal 2013; and 3) a reduction in net revenues of approximately $2 million as a result of lower shipments into Venezuela due to the economic instability occurring there.” They note that the decrease in the Americas was focused in North America and expect continued “negative impact” on the North American wholesale business “in the near future.”

I love that DC fell because they were controlling distribution. Staying far, far away from Venezuela right now is a good idea.

In EMEA the Quiksilver brand was down a low double digit percentage. DC fell by high single digits and Roxy was flat. “The decrease in EMEA wholesale channel net revenues was primarily due to lower net revenues with clearance customers due to improved inventory management, and increased returns and markdowns to aid inventory sell-through versus the prior year period.”

In APAC “…segment net revenues increased across all three core brands (Quiksilver, Roxy and DC) and all three distribution channels (wholesale, retail and e-commerce). A significant portion of the net revenue increases was driven by promotional activity and clearance sales.” APAC revenues rose 11% in constant currency but were down 4% as reported, and they expect currency to continue to be an issue in that region “in the near future.”

As reported, here’s how Quiksilver did during the quarter by distribution channel.

Talking about the wholesale business, they note, “Our wholesale net revenues have declined for the last several quarters, particularly within the Americas and EMEA segments due to various economic and competitive challenges. We believe it is likely that such difficulties will continue in the near future, resulting in further net revenue declines within this channel.” Ecommerce revenues in the Americas were down slightly. CEO Andy Mooney noted in the conference call that they expect more fallout in the “smaller wholesale accounts.”

Gross margin in the Americas rose from 42.8% to 43.4%. In EMEA it was up barely from 58.7% to 58.8%. In APAC, it fell from 54.0% to 52.7%. The overall gross profit margin remained the same at 50.9.

Selling, general and administrative expense (SG&A) declined by 5.6% from $216 to $204 million. These expenses include $2.6 million this quarter and $3.1 million in last year’s quarter as part of the profit improvement plan (PIP). There’s another $2 million in expense during the quarter “…related to certain non-core brands that have been discontinued, but I don’t know if that’s part of SG&A or cost of goods sold. As a percentage of sales, SG&A declined from 52.5% to 51.9%.

They point out that, “Depending on the pacing and nature of further restructuring activities, we may not be able to maintain the same pace of SG&A savings in future quarters that we have achieved in recent quarters.” There’s no “may not” about it. A company’s ability to improve the bottom line through expense cuts doesn’t last forever. Employees won’t work for free and landlords will want their rent.

Remember, the PIP is supposed to improve adjusted EBITDA by $150 million by the end of fiscal 2016. “Approximately one-half of this improvement is expected to come from supply chain optimization and the rest is expected to be primarily driven by corporate overhead reductions, licensing opportunities and improved pricing management, along with net revenue growth.” They aren’t specific about which part will provide how much.

The operating loss fell from $9.7 to $4.8 million, but a chunk of that ($2.3 million) is because of a decline in the asset impairment charges from $3.2 million to $883,000. It’s good to see those noncash, but indicative of expected future cash flow, charges going away.

Interest expense rose from $15.5 to $19.4 million, and the loss from continuing operations after taxes declined from $31.2 to $22.7 million. However, they had a tax benefit of $4.4 million instead of a tax expense of $2.9 million, a $7.3 million improvement.

Net income went from a loss of $30.6 million to a profit of $14.9 million, but that’s only because they had a one-time $37.6 million gain from discontinued operations after taxes.

I’d characterize the balance sheet as weaker than a year ago. Equity has fallen from $590 to $380 million while total liabilities are up from $1.158 to $1.221 billion. Total borrowings rose over the year from $788 to $865 million. There’s a decline in inventory from $419 to $360 million, but it’s hard to evaluate that as some of the reduction came from the sale of assets or elimination of brands. CFO Shields tells us in the conference call that inventory days on hand decreased by 11 days. He also says, “The quality of our inventory improved as we continued to liquidate aged inventory.” Aged inventory as a percentage of total inventory was down. That, I suppose, is good, but some specifics would sure be nice. When will that excess aged inventory be gone and how much are we talking about?

Receivables are pretty much unchanged at $339 million. I might have expected some reduction there given the sales decline and asset sales.

Okay, having dragged you through the numbers, let’s have some fun and talk strategy. At various points in the 10Q and the conference call, we’re reminded that margins at wholesale were down, that the number of smaller wholesale accounts is shrinking and that they expect it to continue to shrink. That’s just a market reality faced by all brands. CEO Mooney notes, “The smaller accounts are absolutely important to us. I just think there’s going to be fewer of them." In the U.S., we learn, small wholesale retail accounts are just 19% of Quiksilver’s revenue. In Europe, it’s 40% to 45%.

If that channel is going to continue to shrink, Quik can’t rely on it for growth. What’s the solution? One answer, they believe, is more retail stores. They ended the year with 645 company owned stores and expect to open around 40 more this year.

A second thing they are doing is adding entry-level price point products for DC. I don’t know what kind of revenue that might generate. I’m mostly just surprised they weren’t selling there before. So was Andy Mooney I think. He notes that DC has never participated in the “…$45 to $55 retail price segment for canvas vulcanized footwear…” Worldwide, he estimates the market is 120 million pairs. You can see why he’d like DC to get a piece of it. I can’t think of any reason they shouldn’t.

Third, we find out that Quiksilver has already reduced product SKUs by 40%, but that their own retail stores can still only showcase half the company’s products. He thinks they might be able to cuts SKUs by another 40%. Think of the magnitude of those cuts. It’s stunning that they could have had so many SKUs in the first place.

Cutting SKUs that much has huge implications for inventory investment and supply chain management. It will let them pull a chunk of working capital out of the company. But maybe more important is the impact on their competitive positioning when retailers have some chance to actually get theirs heads around a brand’s line and merchandise more of it well. As they cut SKUs and manage distribution better, there is an opportunity to differentiate the brands.

But my antenna really went up when Andy said early in his remarks, “…we also believe that we have opportunities to increase sales to the larger wholesale accounts in these markets by focusing on appropriately segmented product collections.”

Later, in response to an analyst question, he expanded on his thinking:

“…I think increasingly, the larger retailers aren’t really interested in what our line is. What they’re interested in is what their line is. Each of those retailers is increasingly looking for custom-design lines that appeal to both their unique consumer as they see it, and certainly their business objective.”

He goes on:

“Every retailer in the mall is looking down the mall to see what the competitor has from the same brand. And if they have something similar, they’re not particularly interested in carrying that brand. So that requires an organizational setup, people who are adept to doing footwear under [indiscernible] and that’s a particular breed of cat. You need a supply chain that can get both in printed goods and cut and sold goods to market on a quicker pace than you would do for the traditional channel.”

Okay readers, help me out here. I read that and hear “fast fashion in big chains.” I’m not prepared to characterize this as a good idea or a bad idea, but I do have questions. Just to be clear, I don’t have any problem with Quik’s brands being in large chains (the right one, merchandised correctly, with the right product). Everybody else is there and, as Andy Mooney says, this is where the market is going.

Question one is does Quik have the systems and infrastructure to pull this off? CEO Mooney says they do. The company will have to develop a new internal attitude about how they operate.

Question two: Does this imply selling to some different retailers than they are already selling to? If so, which ones?

Question three: What exactly does it mean to produce different products for different retailers? How different are the products? How many products how often? Is it for the whole line that the chain carries or just some coordinating product around the edges?

Question four: If retailers are interested in what their line is, not what your line is, what does that say about brand positioning? Do you just make what they want? I think this might say something important about how you compete. How much influence does a chain that places a big order have over the product you make before you aren’t managing your own brands anymore?

Question five: Who is Quik competing with in this market with these customers? What’s the value of their brand’s heritage in these circumstances?

I’ve wondered a few times now if distribution won’t begin to become less important as you allow consumers to connect with your brand whenever they want and however they want on whichever device they are using or in the store, where the devices are also used. I suspect that’s part of the answer to making this work.

At the end of the day, I’m on board with the operational steps Quik is taking to cut costs and improve efficiencies and expect it to have a positive impact on the bottom line. I think I mostly agree with their ideas about how the market is evolving. But figuring out how heritage brands fit in this market and grow in it is the challenge they have.

Not for the last time, and not just for Quiksilver, I wish they were a private company.