VF’s Management Process and Strategy: Thoughts on Their Annual Report

I’ve spent some time on VF’s 10-K filing for the year ended December 31, 2017. It was a thought provoking read (yes, I know I’m the only one who would say that about a 10-K) that left me thinking about how VF tries to derive its competitive advantage. There are some lessons in it for all of us who sell products that are an awful lot like your competitors’ products. Here are some VF facts on which we can base the discussion. I’ll also review their numbers for the year.

- More than 30 brands (23 of which they call primary) divided into three segments; Outdoor & Action Sports, Jeanswear, and Imagewear. Vans, The North Face, Timberland, Wrangler and Lee are the five largest.

- They sell through specialty stores, department stores, national chains, mass merchants, and through theirs owned brick and mortar and online retail. In international markets, they also sell through licensees, agents, distributors, and independently operated partnership stores.

- 65% of revenue is from the Americas, 24% from Europe, and 11% from Asia-Pacific region.

- Total revenue for the year was $11.8 billion.

- Direct to consumer revenues were 32% of total revenues. At the end of the year they had 1,518 stores worldwide, opening 111 in 2017. They also have 1,100 “concession retail stores” mostly in Europe and Asia.

- Vans, Timberland, The North Face, Kipling, Dickies, Lee, Napapijri, and Wrangler have stores under their names that sell only that brand’s products. There are also 80 outlet stores that sell many VF brands.

- Ecommerce is 21% of direct to consumer.

- VF owns 21 factories and produced 23% of 473 million units there. It works with approximately 1,000 other factories in 50 countries. It has 38 distribution centers.

Consider the complexity. How many combinations of where it’s made, where it’s sold, how it’s distributed, who the customer is and how the brands are positioned against each other (where that’s an issue) are there? That’s a big, big number. To some extent, it’s simplified by the fact that the five largest brands are a big chunk of total revenue, but still, this is quite a management challenge. Here’s how they describe part of it in the 10-K.

“Managing this complexity is made possible by the use of a network of information systems for product development, forecasting, order management and warehouse management, along with our core enterprise resource management platforms.”

Talking about how VF manages its manufacturing base, the 10-K says:

“Products manufactured in VF facilities generally have a lower cost and shorter lead times than products procured from independent contractors. Products obtained from contractors in the Western hemisphere generally have a higher cost than products obtained from contractors in Asia. However, contracting in the Western Hemisphere gives us greater flexibility, shorter lead times and allows for lower inventory levels. This combination of VF-owned and contracted production, along with different geographic regions and cost structures, provides a well-balanced, flexible approach to product sourcing.”

CEO Steve Rendle’s nearly full-time job must be getting quality people he trusts into the right positions. They had 69,000 employees at the end of the year. He notes in the conference call, for example, “To support the execution of our strategy and better enable the growth of our large global brands, we have realigned the roles of our Group Presidents and redirected our leadership talents at our most important objectives. Going forward, each Group President will be responsible for a single geographic region and have one global brand reporting to them.”

So, what are the foundations VF builds its business on? People (like any organization), systems, procedures, and disciplined management processes.

Oh – wait – I didn’t say brand or product. From the 10-K: “In addition to the design functions of each brand, VF has three strategic global innovation centers that focus on technical and performance product development for apparel, footwear and jeanswear. The centers are staffed with dedicated scientists, engineers and designers who combine proprietary insights with consumer needs, and a deep understanding of technology and new materials. These innovation centers are integral to VF’s long-term growth as they allow us to deliver new products and experiences that consistently delight consumers, which drives organic growth and higher gross margins.”

I’m guessing they have one innovation center focused on each of their geographic areas. For certain of their brands (surely the top five) they have enough size to develop, if appropriate, area specific product.

They can do this because of their size. But size can be dysfunctional if you don’t have the four foundations I mention above. What are the other benefits of being this big and managing like VF tries to?

Higher gross margin. Your volume, number of contract manufacturers, and having your own factories will give you some advantage.

Lower advertising and promotion expense as a percent of sales. They spent $716 million, and in fact have accelerated their brand building spending, but it was just 6% of revenues.

More flexibility and faster response to market changes. Anybody think that’s competitively useful these days? It’s valuable in brand building but having the ability to make some product quickly and perhaps in smaller quantities rather than making too much of the wrong stuff is also good for your margin. There’s also value in having a distribution network that lets you move product around in response to changes in demand. Also improves inventory control which, I believe, helps with brand building.

The cost of increasingly complex logistics and important systems is more efficiently spent. That is, VF, as an $11 billion business, doesn’t have to spend 11 times as much as a $1 billion business.

As I watch companies like VF focus on flexibility and shorter product cycles, I continue to wonder about the changing role of trade shows. For certain products, they seem built on the assumption of product cycles that increasingly don’t address what the market and end consumer want and when they want it.

Let’s move on and look at the numbers.

VF showed a revenue increase of 7.1% in 2017 from $11.0 to $11.8 billion. $489 million was from existing brands and $247 million from the Dickies acquisition. $49 million was from a positive foreign currency impact. The gross margin improved 1.2% to 50.5%. “…reflecting a 180 basis point benefit from pricing, a mix-shift toward higher margin businesses and lower restructuring costs, which was partially offset by a 60 basis point impact from foreign currency.” SG&A expenses grew 11.9% from $3.99 to $4.46 billion. As a percentage of revenues, it was an increase of 1.6%. “This increase is primarily due to investments in our key growth priorities, which include direct-to-consumer, product innovation, demand creation and technology initiatives. The increases were offset by lower restructuring costs in 2017 and a pension settlement charge of $50.9 million in 2016, which did not recur in 2017.”

Operating income rose from $1.368 to $1.503 billion. Interest income rose from $9.2 to $16.1 million while interest expense was up from $94.7 to $102 million.

Income taxes rose from $206 to $695 million. The new tax law passed in December resulted in a $465.5 increase. That’s tax on income that had been earned and held offshore. It’ a one-time thing. The result was a 42.7% decline in net income from $1.07 billion to $615 million.

As you probably know, VF acquired Dickies in 2017 and has put Nautica up for sale. On the income statement, they separate discontinued operations, and provide separate information on the late in the year acquisition of Dickies. I’m not breaking any of that out in my discussion and want to explain why.

The first of four long term drivers of their strategies is, “Reshape our portfolio. Investing in our brands to realize their full potential, while ensuring the composition of our portfolio positions us to win in evolving market conditions.” Buying and selling brands is part of their normal operations. They are very disciplined about what they buy and how much they will pay. They don’t necessarily buy something every year, but it’s an active and ongoing part of their operations and I don’t believe in viewing their results net of it.

Acquisitions remain a top priority for VF as they are “…transforming VF into a more digitally-enabled consumer and retail-centric organization.”

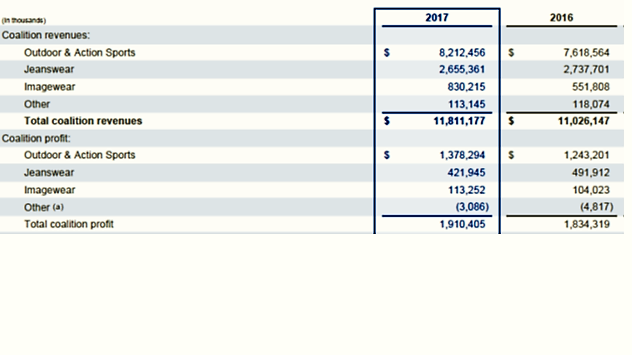

Below are revenues and operating income by segment- what they call coalitions. The key thing to notice is that Outdoor & Action Sports provided 69.5% of revenue and 72% of operating income.

Vans’ revenues were up 17% in 2017. The North Face was up 4% and Timberland 2%. Total segment revenues were up 8% for the year.

“Global direct-to-consumer revenues for Outdoor & Action Sports grew 17% in 2017, driven by an expanding e-commerce business, comparable store growth and a 1% favorable impact from foreign currency. Wholesale revenues increased 2% in 2017, driven by growth in the Vans brand and Europe, partially offset by the above-mentioned U.S. retailer bankruptcies, lower year over- year off-price shipments and efforts to manage inventory levels in certain markets.”

The dominance of and dependence on Vans, as well as its continued and rapid growth is rather remarkable. You won’t be surprised to learn that CEO Rendle lists “…protecting and enabling the explosive growth in Vans…” as the first of their 2018 top priorities. VF expects “…high-teen growth from Vans through the first half of this year.”

During the conference call, an analyst asks the following question, which has been on my mind for a while as well.

“You talked about protecting the brand. You talked about not letting it overheat. What does that mean to how you’re going to manage the brand into the wholesale channel and your DTC, right? Are you going to constrict some of the deliveries into the wholesale channel? Are you going to limit some of the inventory across the channel? Are you going to segment the styles further? How do you plan to maintain a double-digit growth rate, as you alluded to, so that this doesn’t roll over, like we’ve seen other brands do in the not-too-distant past?”

Good question. You can read into it the inevitable and often discussed in Market Watch public company problem; How do you grow without screwing up the brand? Here’s part of Steve Rendle’s answer.

“…our Vans team is really the benchmark business on how they look at product segmentation across the different consumer touch points that we have to sell into, with our stores being the most premier expression of our brand. They’re really evolving how they’re looking at using stores and coming up with a mix of formats that play into the specific communities across the globe, but being very thoughtful, and direct partnerships with those wholesale partners, placing the right amount of inventory, being very thoughtful about not having one style over-torque, but really having it be a balanced approach with the right amount of newness to keep the brand moving forward each season.”

His answer sort of comes down to, “We manage the brand better than other brands are managed.” Apparently so. Yet it doesn’t really address the public company conundrum and I’ve never known a brand that didn’t, eventually, hit a dump in the road- “roll over” as the analyst puts it. And I wonder, given the relative growth rates, why they can’t manage The North Face and Timberland as well as they are managing Vans. It has something to do with the brand and the competitive environment, not just the brand management it seems.

Given the dependence on Vans, I hope they can continue to be disciplined in how they grow sales while protecting the brand.

A quick note on “risk factors” as listed endlessly in the 10-K. I used to spend a lot of time on them. Now, I find myself skimming them and rarely having anything to say about them- and not just for VF. That’s because risk factors seem to be evolving from meaningful business considerations to a list of anything that the lawyers think could possibly go wrong. They aren’t written to inform investors as much as to protect the company.

The balance sheet is weaker compared to a year ago. Total equity fell 25% from $4.9 to $3.72 billion. The current ratio is down from 2.4 to 1.5 times and cash declined from $1.227 billion to $566 million. Debt to total capital was up from 31.9% to 44%.

The growth in receivables and inventories seems consistent with revenue growth and the acquisition of Dickies. Also due to the Dickies acquisition, short term debt jumped from $26 to $729 million. Hope they can refinance that before rates rise. Long term debt was also up a bit from $2.04 to $2.19 billion.

The percent of their earnings they paid out as dividends was 96.2%. That’s up from 59.9% last year and 38% in 2013. It’s not that the balance sheet is weak- it’s just not as strong as it was. If I were an investor in VF, the balance sheet changes and payout ratio would leave me wondering what happens if Vans should hit that bump.

The majority of VF’s growth for the year came in it’s fourth quarter, when revenues jumped 20.5% from $3.04 to $3.65 billion. They reported a loss of $90 million in the quarter but remember the big accrual for taxes they were required to take due to the new tax law. Vans, by the way, was up 35% in the fourth quarter, which puts some perspective on the 17% growth for the year.

Like all companies, VF tries to put its best foot forward in its public filings and conference calls. I’m sure they have as many things go wrong as the next company. Still, I walk away from reading their 10-K (and that of some other companies) with a strong sense that what used to give smaller companies a chance for an advantage is no longer exclusively available to those smaller companies.