Zumiez’s Annual Results; And Tales from its Conference Call

My favorite part of a Zumiez’s conference call is when CEO Rick Brooks apparently decides the analyst has asked the wrong question or doesn’t quite understand the implications of what’s been asked. Two plus pages of transcript later, sometimes ably supported by CFO Chris Work, we may have forgotten the original question, but we’ve always learned something new and intriguing.

So it was for the recent call discussing the quarter and year ended February 3rd, 2018. But before we have that fun, let’s go through the numbers.

The Numbers

Fourth quarter revenues rose 16.9% from $263.6 to $308.2 million. “Contributing to this increase were positive comparable sales growth of 7.5%, the net addition of 13 stores since the end of last year’s fourth quarter, the 53rd week in 2017 were $10.3 million and the positive impact of foreign exchange were at $5.3 million. Also benefiting fourth quarter 2017 net sales is an adjustment to deferred revenue related to our STASH loyalty program were $3.8 million,” explained CFO Chris Work.

The gross margin rose 1.5% to $37.2% compared to last year’s fourth quarter. Chris notes, “The increase was primarily driven by 120 basis points of leverage in occupancy, 80 basis points related to the recognition of deferred revenue due to changes in our STASH loyalty program, estimated redemption rate, and 70 basis points of improvement in product margins. These increases were partially offset by 70 basis point increase in inventory shrinkage and 20 basis point increase in incentive compensation. Inventory shrinkage has been difficult for us in 2017.”

I’d say it has been. When your improved product margin is 100% eaten up by disappearing inventory, it’s a problem. Zumiez has always tried to drive responsibility down to the store level. Remember that a year or two ago, they transferred responsibility for online sales to their stores? I’m wondering if that isn’t somehow related to the shrinkage problem.

SG&A as a percentage of sales for the quarter rose just slightly from 25% to 25.2%. “The…increase was primarily driven by 100 basis point increase related to our annual incentive compensation partially offset by 40 basis points of leverage in our store operating cost and 30 basis points of leverage across other corporate costs.” I never mind seeing incentive compensation expense rise, as it’s indicative of good results.

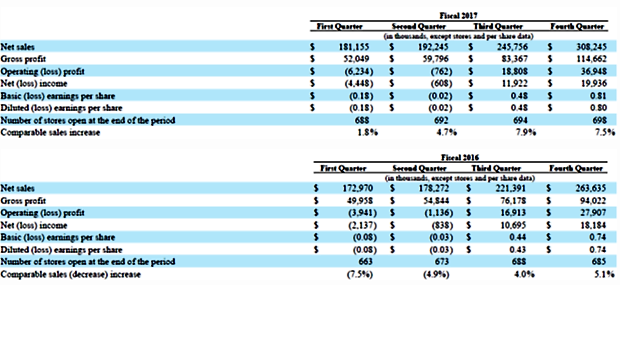

Net income for the quarter rose 9.6% from $18.2 to $19.9 million. For some perspective, the chart below shows the quarterly results for the last two years.

Zumiez ended its year with 698 stores; 607 in the U.S., 50 in Canada, 34 in Europe, and 7 in Australia. The number of new store openings, especially in the U.S., is declining. But Zumiez has been telling us that would happen for some years. Over the last three years, stores opened has declined from 57 to 28 to 17. The 2016 number of 28 was impacted by the acquisition of five stores in Australia. The estimated number for this fiscal year is 13 new stores worldwide.

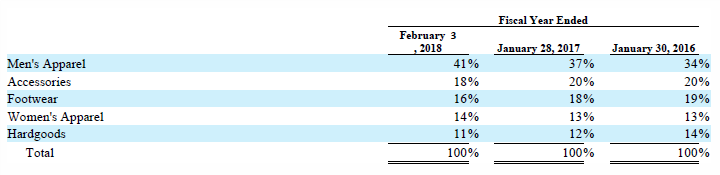

The chart below shows the composition of sales by category during the last two years.

It’s always intrigued me to see how much revenue is from men’s’ apparel compared to women’s. It seems unusual for a mall-based retailer (if I can still classify Zumiez that way?). I don’t know if it’s a problem, an opportunity, or a competitive advantage. Also note the decline in hard goods as a percentage of revenues- takes up a lot of room but doesn’t offer great margins. But it’s an important part of Zumiez’s market positioning.

For the whole year, revenues roses 10.9% from $836 to $927 million. Sales in the U.S. were $774 million, or 83.5% of the total. In fiscal 2016, they were $711 million, or 85% of the total. “The increase reflected a $48.6 million increase due to comparable sales and a $23.6 million increase due to the net addition of 13 stores (made up of 12 new stores in North America, 5 new stores in Europe, and 2 new stores in Australia offset by 6 store closures). Net sales include $10.3 million related to the additional week in the 53-week period and a $6.3 million increase due to changes in foreign currency rates.”

Zumiez’s business in Europe has not performed as management hoped. They’ve had some losses there. As Chris put it, “…we have not had the results from the investment we’re hoping [for].” Rick Brooks talks about the “amazing results” they had in 2015 driven by a “…really huge long board trend and then in 2016 it basically completely reversed and of course we were still playing out as Chris said investing and building the business at that point when sales actually went – got considerably more difficult relative to what we assumed to be appropriate pace of growth at that point.”

By 2015, most of us were amazed the long board market hadn’t cracked already, but none of us had any doubt it was going to. Because that’s what bubbles do. If Zumiez was looking at success with their European acquisition that they could see was overly reliant on one product category, perhaps they could have called it out. But who want to sound a note of caution on a new (second half 2012) acquisition you paid a hefty price for.

Zumiez launched “…over 150 new brands…” during the fiscal year. It was just last year they were saying they tended to launch 100 a year. These are not Zumiez owned brands, but brands where Zumiez works with the owner at various levels to launch them in Zumiez stores.

The gross margin rose to 33.4% from 32.9% the previous year. “The increase was primarily driven by an 80 basis point impact due to leveraging of our store occupancy costs, 30 basis points related to the recognition of deferred revenue due to changes in our STASH loyalty program estimated redemption rate and 20 basis points on product margin. These were partially offset by 60 basis points in higher inventory shrinkage and 10 basis points due to higher annual incentive compensation.”

Net income rose 3.5% from $25.9 to $26.8 million.

There’s no need to discuss the strong balance sheet, except to remind you of the competitive advantage it offers, allowing you to pursue your strategy and initiatives even in the face of a bump in the road.

One last financial note before we get to the fun stuff. Zumiez 10-K includes the following risk factor: “The reduction of total outstanding shares through the execution of a share repurchase program of common stock may increase the risk that a group of shareholders could form a group to become a controlling shareholder.” It’s last in a list of many risk factors.

Companies, as you know, have been buying back their shares to boost their earnings per share. Some (not Zumiez) have been borrowing money to do it and leveraging up their balance sheets. We’ll see how that works out as interest rates rise.

Share buy backs are inevitably touted as a benefit to shareholders though you might also view buy backs as an admission by management that they can’t figure out any good investment opportunities in their business. I find it amusing that this benefit requires a risk factor in the 10-K. You might also consider that if the buy backs reliably raised the share price consistent with the reduction in shares outstanding, the cost to a potential controlling shareholder, in dollar terms, doesn’t change. If that were the case, I don’t think a risk factor would be required.

Tales from the Conference Call

Now for the fun stuff. I’m not going to start by reviewing Zumiez’s Competitive Strengths. They are the same they’ve been for 20 plus years and, most importantly, work in any retail environment. Instead, I want to remind you of two issues I’ve written about- not just related to Zumiez.

I’ve characterized the term “omni-channel” as the authoritative sounding word legacy brick and mortar retailers have used to make it sound like they’ve got things under control and know how to manage the brave new retail world where the consumer is in charge. I’ve also stated that doing ecommerce right is a continuingly expensive undertaking. Unless you can generate enough incremental revenue and operating income to at least pay for it, you are failing.

Being online- selling on line- having web sites and connecting ecommerce with brick and mortar do not represent a strategy. They are the necessary tools for implementing a strategy.

“We believe now we’re entering into a new phase in servicing our customer,” says CEO Brooks, “moving beyond omnichannel into a new consumer environment with yet higher expectations. While we’re not sure what to call this new consumer phase, the New World will be characterized by key themes and words, such as trade area, localization, optimization, speed, intimacy, engagement, connection, innovation, and community.”

I’m relieved I’m not the only one who doesn’t know what to call it. If Rick’s descriptors of the consumer environment are reasonably accurate, or at least not too far off from what the future holds, they are the basis for a strategy using the tools Zumiez has in place or is developing. If forced to reduce his already short list of words, I come down to flexibility and informational immediacy. Let’s talk about some things Zumiez is doing to succeed in the world Rick is describing.

As you know, Zumiez introduced 150 brands in fiscal 2017, up from around 100 the previous year. At this point, I imagine Zumiez has a robust system for onboarding, and offboarding when they don’t work out, new brands. In the environment Rick describes, imagine the value of seeing these new brands and the trends they may, or may not, represent when they are still small and, for lack of a better word, pure. How else does a retailer find enough new brands to satisfy the consumers’ requirement for constant newness?

Zumiez’s largest third-party brand accounted for 8.5% of revenues in 2017. That’s up from the previous two years. Meanwhile, Zumiez’s private label revenues have fallen over three years from 21% of revenues to 20.2% and 16.8% in 2017. Given the emerging competitive environment, I wonder if the Zumiez management team might not be conflicted if private label (regardless of the margin) grew too much or a single brand became a larger chunk of total third-party revenues.

Obviously, Zumiez’s size and resulting ability to support the new brand process gives it an advantage. Here’s how they describe it in the 10-K. “Given our scale and market position, we believe that many of our key vendors view us as an important retail partner. This position helps ensure our ability to procure a relevant product assortment and quickly respond to the changing fashion interests of our customers. Additionally, we believe we are presented with a greater variety of products and styles by some of our vendors, as well as certain specially designed items that we exclusively distribute.”

Zumiez’s new brand process isn’t restricted to the market the brand originated in. Says Rick, “…we have brands as well as trends that are already flowing across the oceans for us and working on multiple continents.”

Finally, Ricks longest answer to a short question highlighted another Zumiez’s advantage I, I’m embarrassed to say, hadn’t focused on before. You know that Zumiez has trade areas, and the goal is to maximize revenue from that area, not just to open new stores in it. You might find yourself closing stores to grow revenue. You also know that Zumiez has transferred ecommerce fulfillment to their stores. I always thought that was a great marketing/customer relations thing to do.

I hadn’t focused on the financial benefit.

“…when our web business grows digital sales today, we’re now able to lever physical store, our physical store cost structure,” says Rick.

“Lever our physical store cost structure.” Just a few little words. Where the hell has my mind been! Zumiez is in the process of solving the problem of making the cost of the “omnichannel” pay off. By having fulfillment done through the stores they’ve made what used to be two cost centers into one and made that one more efficient. Completely in sync with their customers, Zumiez literally doesn’t even have to think about whether it’s an ecommerce or a brick and mortar sale. They don’t care because there’s largely just one cost structure. Rick continues:

“…this is one of the measures of what you mean when you say you have an integrated seamless experience right, you have to integrate it into everything you do in the service of customers. And of course our store teams and digital sales teams they all work as an integrated unit now, looking at all the touch points and how we can best drive consumers to whatever channel the empowered consumer prefers.”

“Probably the easiest example, Sharon, I could give you of evidence here about this idea of how we’d recreated this kind of new integrated business model is localized fulfillment. So through localized fulfillment and in particular already our order routing algorithms, we’ve now levered store payroll and our other store cost structures in two successive holiday seasons. And when I hear a lot of retailers talk, they talk about how a significant growth in web revenue is de-leveraging their business.”

Brick and mortar retailers were initially dragged into ecommerce as a defensive measure focused on giving their customers what they wanted. Zumiez has said that with their trade areas, new systems, and brick and mortar responsibility for ecommerce, they have figured out how to synchronize market and financial imperatives.

Can you make ecommerce a competitive positive if you don’t do that? I’m guessing no and expect all successful retailers with a brick and mortar footprint to have to do the same as Zumiez.