As I explained in an earlier article, my usual detailed analysis of company income statements and reports for quarters ending March through May went on hiatus. It didn’t seem useful given the initial disruption caused by the virus and lockdown. Not writing doesn’t mean I wasn’t reading. In no particular order, I reviewed VF, The Buckle, Tilly’s, Abercrombie & Fitch, Zumiez, Hibbett Sports, Dicks, and Deckers.

Hey, it’s good to have something to do when you can’t go to a restaurant, theater, gym, store, vacation, golf course (thankfully ended) and are threatening to run out of house projects.

This article isn’t about any of the listed companies. It’s about all of them. There are certain commonalities, trends, and uncertainties we should (hopefully do) have top of mind as we take this epic journey that increasingly looks to be lasting a while.

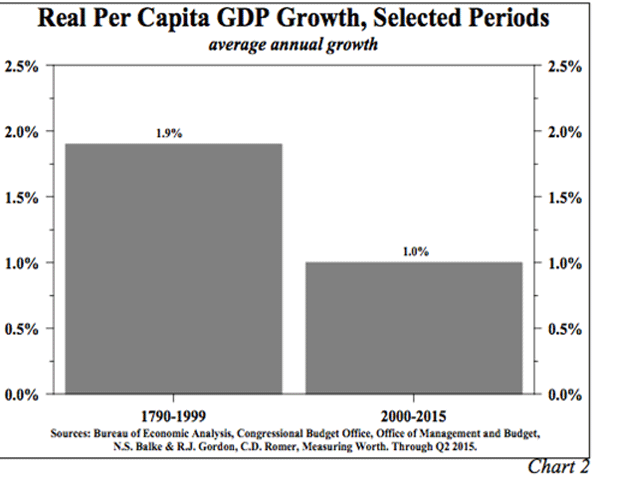

To set the stage, please go read this article by John Mauldin, whom I have a lot of respect for. You won’t like it- I don’t like it- but I’ve never thought it was my job to help you think happy thoughts. John is telling you something important more succinctly than I could (and with better charts!).

The 10-Qs and 10-Ks all show better results if the reporting period ended earlier in the year. No surprise. The average, unweighted, year over year quarterly revenue decline was 27.6%. Take out VF and Deckers, with March 31 quarters and revenue declines of 11% and 5%, and you get a decline of 34% for those with later ending quarters.

Each has a section in their filings on the impact of the virus and the actions they have taken. They are almost interchangeable. Drawing down credit lines, furloughing employees, protecting the health of employees and customers, negotiating with landlords (or just not paying rent), cancelling or reducing orders, and stopping share buybacks are common actions.

It’s a reaction to a set of unprecedented circumstances and a level of uncertainty nobody managing a business has ever experienced. If you take the time to review the “Risk Factor” section of some of these filings, it will strike you that their significance has changed. They are no longer statements of possibilities the lawyers required. They now represent real issues impacting companies.

“We’re screwed if our supply chain was disrupted,” a common risk factor might have said, though in better legalese. “Oh yeah, I guess, but that’s not going to happen,” you used to think. Oh wait- it just did. I don’t know where you shop for groceries, but at the local Fred Meyer, shelves aren’t as full as they used to be. If the supply chains are allowed to adjust, they will. But it will take time.

On the plus side, I guess, I’m getting some remarkable buys on wine that’s not being sold to restaurants. Diane and I are actually converting the hall coat closet to wine storage. Look, if you can’t go out as much, which do you need more- coats or wine?

Conference calls and conversations with managers told me of some pent-up demand and optimism from some industry companies as reopenings began. Those were the days of the hoped-for V-shaped recovery. That’s not happening. I’ll say again that I expect this to be the worse recession since right after World War II. And it is happening worldwide in a way no other recession ever has.

Those of you who think the virus caused the recession should know that the National Bureau of Economic Research, responsible for telling us when recessions start and stop, announced on June 9th that the recession began in February- before the virus took hold. Meanwhile, I’m guessing you’ve noticed that it’s surged in many parts of the country. Maybe we just got too comfortable with the virus being around, but I think even a modicum of national leadership might have kept this mess from getting quite so bad.

The last piece of bad news is that this recession has happened when debt around the world is at unprecedented levels and will continue to climb. That’s important. What the research shows is that the positive impact of more spending on GDP, when it’s funded by debt, is much lower when debt is already high. If you’re interested in the overwhelming evidence this is accurate, go to this page and read the article at the top of the list called “Quarterly Review and Outlook; 2nd Quarter 2020.” It’s pretty short, but not an easy read.

Sorry for all the bad news. Regular readers know I made the decision years ago to say what I thought the data supported, even when I knew it wouldn’t be popular. Somebody has to. As always, please feel free to tell me if you think I’m wrong.

In these circumstances then, what matter?

Your balance sheet and, yes, I know you know I was going to say that. I won’t spend any time on it except to say that a strong balance sheet is a critical determinant of your ability to be flexible and, bluntly, to just come out the other side of this. Outlasting your competition as a strategic objective sounds harsh, but there you have it.

Data. You need it, it better be good, and I hope you started upgrading systems and optimizing for flexible, algorithmic data collection long before now. Your financial model is changing. Not just some higher costs due to the virus, but different costs. Customer behavior is changing (duh). As a result, I’m fairly sure some of your KPIs (key performance indicators) are changing.

Let’s focus on inventory. Yours and everybody else’s. Remember what happened when The Sports Authority went belly up and the inventory from their 400 stores, was dumped on the market? I’d expect this to be a lot worse. It includes not only the inventory from companies going out of business, but those desperately trying to raise cash (which is pretty much everybody), and the product you didn’t take delivery of. Meanwhile, for some unidentified period of time, demand for all that inventory has declined as people increase their savings and lose their jobs (partially offset by government programs, but we can’t pay people $30,000 a year to not work forever).

If you’ve got stable inventory from solid brands and a balance sheet that supports this, consider carrying it over until next year. If you’ve got the balance sheet to do that.

We’ve all acknowledged that the virus is going to accelerate ongoing changes. If the virus takes as long as I expect to be controlled, more of the changes that might have been temporary will become set in stone. What are those changes? I could list the ones we all already know. It’s the ones I don’t know and haven’t imagined yet that worry me.

I was going to ask, “What kind of stores do you need and where?” but that’s the wrong question. The right question- the only question- is “What is your customer’s behavior and how has it changed?” The customer doesn’t care about your distribution channels, your inventory levels, or your supply chain problems. They only care about the convenience of getting what they want, when they want it, the way they want it.

If you agree and think I’m not too far off on my macroeconomic analysis, then consider the implications for the importance of data.

Now can we ask how many stores, what size and where? Uh, well, except we can’t until we’ve got a handle on our inventory- how much is where, how is it selling in different stores, how quickly can we move it around, which stores are also distribution centers, how quickly can we replenish it and, ultimately how much of what do we really need?

Some of those are old questions that go back to when the first retailer opened the first store. But with those answered can we get back to where and how big stores should be? Sorry, no. We need good data on our online efforts and how customers interact with us online. How do online and brick and mortar impact each other? What is the impact of opening or closing a store on online sales?

I could go on. There is an immediate and massive interdependence of functions that just didn’t happen in the past when things could move slower. No that’s wrong- the interdependence always existed. But the required speed of the response has accelerated and the granularity expanded. You can/have to make more changes in many smaller things faster. Your business has to become a dynamic programming model. Bluntly, I don’t see a way to manage lacking high quality and evolving integrated data systems. Once, having that kind of data was a competitive advantage. Now it’s just a price of entry.

You’ll know you have it when the answers you get surprise you and provide new insight into customer behavior. At the tip of the spear, as algorisms improve, expect your systems to tell you to make, or they make for you, adjustments that initially seem wrong, but that work.

Aside from letting you identify and serve your customers better, consider why this is important to what I think is your new business model. Most industry companies are going to take some revenue hit for some unknowable period of time. If we go back to some forms of locking down, it will be worse. It’s true that your online revenue will rise, but it won’t make up for the decline in brick and mortar. Yes, I know there are exceptions.

Product costs in general will rise not just because of supply chain disruptions but because of inflation. But not just yet. This ongoing form of magic money creation, historically, has always led to inflation, but as long as the velocity of money keeps falling, we may escape it. For a while. I expect you will find yourself raising prices to hold margins. Those wonderful new systems of yours are going to be critical for having the right inventory in the right place at the right time and holding those margins.

Many of your will start to optimize your supply chains for reliability rather than lowest cost. Your customers won’t tolerate anything else. This might be an opportunity to focus on higher quality product. I recommend you consider it as a possible point of differentiation.

Meanwhile, at least initially, costs are going to rise especially in relation to revenues. Protection against the virus costs money and will last for an unknown period of time. Meanwhile, and hopefully also short term, closing and opening stores, and managing staffing has some costs. Taxes are going to rise, though not this year.

There is a ballet going on (maybe mosh pit is a better analogy) between working at home, landlords and tenants and malls. Who is going to work from where and pay what for how long? And remember the macroeconomic impact, as malls lose stores, tenants want to pay less, and real estate owners have trouble making their loan payments and lenders have big loan losses.

Ultimately, this all works out after a historically difficult adjustment period. Those of you with strong balance sheets, a solid brand, quality systems and knowledge of your customers can even expect to come out of this in a stronger position.

But it’s going to be a wild ride. The time for more of the same is over. It won’t work. Take chances. It’s less risky than not taking them.

As an afterthought, if you want to get some historical perspective on the political, social and economic situation we’re in, you might read the latest chapter of Ray Dalio’s book on empires and cycles. Here’s the link. It’s all happened before.