It’s interesting to review this recently released 10-Q, as it discusses VF before the recent announcement that they will spin off the jeans business as a separate public company. With hindsight, you can see how their strategy would lead to that decision. I’ll also outline the company’s change in their business segments and, of course, review the numbers. Let’s get started.

Strategy

Here’s what CEO Steve Rendle says in the conference call.

“…we all see that the U.S consumer continues to be open to and motivated to interact with powerful brands, brands that they connect with, brands that provide products and experiences that are relevant to who they are. I don’t think we’re sitting here saying that this is easy…but we — what we’re seeing is that we have a clarity of focus on what our brands stand for, that we’re bringing the best product. And more importantly, big learnings over the last couple of years is really elevating the brand experience in connecting more emotionally with our consumers. We are able to stay at the forefront of the decisions that they have and where they choose to spend their time and money. We see the same to be true in Europe, and we see the same being very true in Asia and I think as we really focus our attention against those key drivers and platforms within our portfolio, we will continue to see our opportunity to connect and maintain those long-term loyal relationships.”

I’d say that’s not the jeans business he’s describing. Like I said, hind sight is wonderful.

Steve is the second industry CEO I know of who’s trying to help the analysts focus on asking the important questions. I was hoping for follow up questions about systems and the different quality of information, changes in how and how fast they make decisions, their view of risk taking and how better/different customer information is leading to changes in logistics and inventory management. Oh well.

Later, talking specifically about Vans, CEO Rendle makes some related comments.

“The strength and understanding of the consumer, that the team has gained through our consumer insights and brand building focus, they just have gotten stronger and stronger, more focused on who they are and more importantly who they are not. We are in exceptional moment where we’re seeing distorted growth. Some of that could very much be some trend, level of trend. But honestly, the way we look at it, we are resetting the rightful level of penetration that this brand has with the consumer and within the wholesale channel and as you — as we do our channel checks, you can see the brand has just taken a larger footprint both on the footwear wall, the tables in the footwear section, but we’re also now starting to place really relevant assortments of apparel. So that the better this brand begins to understand…its consumer, the more thoughtful we can be on placing the right products at the right time. The disciplined franchise management, channel management segmentation just gets stronger and stronger and it really is disciplined of how that team operates… This isn’t an exceptional moment of time that likely has a downward cycle in the back and this is just a reset of its rightful position as one of the top footwear brands in that active lifestyle component of the consumer’s choice.”

You can see Steve alluding to using the same tools/approach for Vans he discussed in the first quote. No surprise there. He also talks about Van’s current growth as “exceptional” and “distorted.” They’re using that as an opportunity for “resetting” the brands penetration and positioning. They are being thoughtful and purposeful in how they distribute the brand. Good.

They see a particular opportunity in Vans’ apparel. It sounds like some cautious management of the brand even as it grows is creating, as they see it, the opportunity for apparel. What I think I hear, and what I imagine they’d like Wall Street to pick up on, is that even if (when?) revenue growth does slow, they could continue to grow the bottom line.

But he doesn’t see that this time of “exceptional” growth as one that will have a “downward cycle in the back.”

Well, that’s walking a fine line. I have endless respect for what VF has accomplished with Vans. If he means the brand isn’t in danger of the kind of blowup we’ve seen in other industry brands, I can buy that giving their management process for the brand as they describe it. But there’s an implication that any kind of turn down isn’t going to happen. That would be somewhere between unusual and unprecedented. Even Nike had its hard times. I continue to believe there’s a limit to one brand’s market share.

If they are saying that by careful distribution, positioning of the brand, and paying attention to the consumer, they can manage and minimize a downturn when it comes, I’d think that right. They may be well positioned to benefit from the inevitable recession.

Vans is taking advantage of its exceptional revenue growth to position the brand for success even when that revenue growth is not quite so exceptional. Good plan.

Housekeeping

VF has changed its reportable segments, joining other companies who have stopped referring specifically to action sports. The new segments are:

- Outdoor, which includes The North Face, Timberland, Smartwool, Icebreaker and Altra.

- Active, which includes Vans, Kipling, Napapijri, JanSport, Reef, Eastpak and Eagle Creek.

- Work, which includes Dickies, Bulwark, Red Kap, Timberland PRO, Wrangler RIGGS, Walls, Terra, Kodiak and Horace Small.

- Jeans, which includes Wrangler, Lee and Rock and Republic.

As we know, those four segments will become three after the spinoff of the jeans business.

CFO Scott Roe tells us why they made the change. “Our Outdoor Action Sports business has become so large that we felt it was good for you the readers to have one click down one more level of visibility rather than having one giant segment, especially given some of the different financial characteristics of the two as you can see, right. And really that’s the driver in the guidance is companies with like characteristics are grouped together and it’s really no more or less than that.”

Makes sense to me.

The Numbers

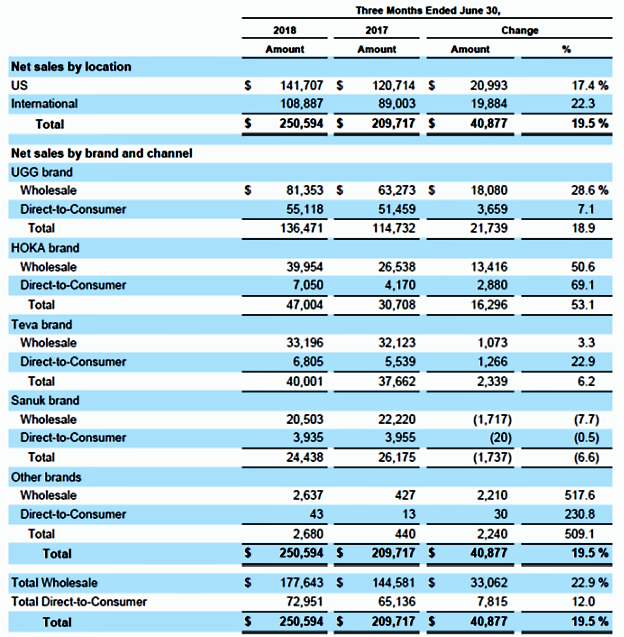

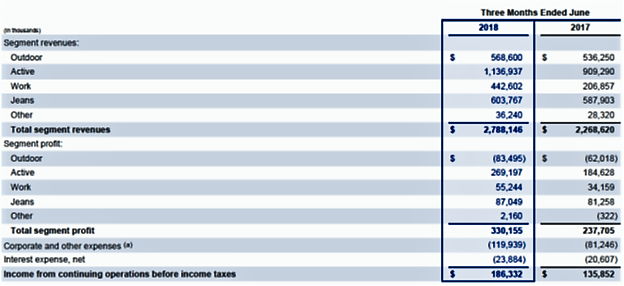

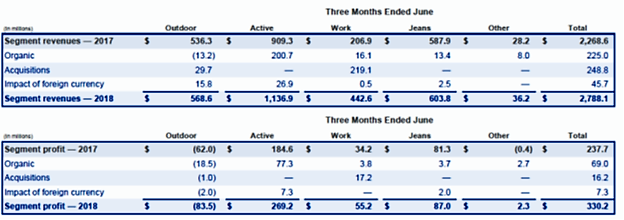

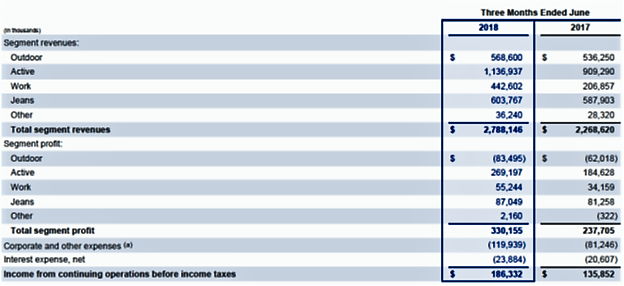

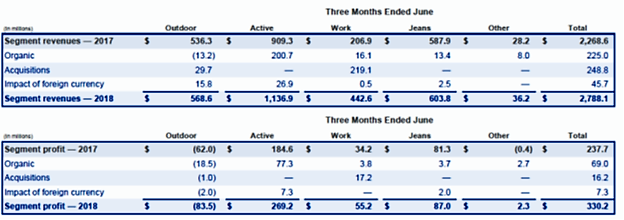

Net revenues rose 22.9% from $2.269 billion in last year’s June 30 quarter to $2.278 billion in this year’s. The table below shows revenue and operating profit by segment. You can see that the active segment, where Vans lives, is still the largest segment, though not as large as before the change described above. Vans was up 35% for the quarter, speaking of unsustainable trends. The big jump in work came from the Dickie’s acquisition. The North Face revenues rose by 8% and Timberland was down 1% despite a 4% boost from foreign currency.

11% of the 22.9% revenue growth came from acquisitions, and 3% from favorable foreign exchange trends. Direct to consumer revenues rose 22% and were 31% of total revenues. Acquisitions accounted for 6% of that growth and foreign exchange 2%. Ecommerce rose 54% including 4% from foreign currency and 21% from acquisitions.

International revenues represented 38% of quarterly revenues and rose 27%. 5% of the increase was from foreign currency and 13% from acquisitions.

56.6% of revenue growth in the quarter came from acquisitions and foreign currency. The table below shows the sources of revenue and operating for both quarters by segment. This is worth spending a minute on.

The gross margin rose from 49.6% in last year’s quarter to 50.3% in this year’s. “Gross margin was favorably impacted by a mix shift to higher margin businesses, increases in pricing and foreign currency changes, partially offset by lower margins attributable to acquired businesses, acquisition and integration costs and certain increases in product costs.”

SG&A expenses as a percentage of revenue declined from 42.6% to 42% due to spreading these expenses over a bigger revenue base.

Net income rose 45.6% from $109.9 to $160.4 million.

One other financial comment that may be of interest to some of you. VF has a defined benefit pension plan, which is becoming something of a rarity in this country. Looking at Note 10 in the 10-Q on that plan, I saw that the discount rate they are using to determine pension obligations was about 4.25%. “So What? How else are you going to bore us today, Jeff?”

I just wanted to congratulate VF on having a reasonable discount rate. The lower the rate, the more it costs them to fund the plan. In the public sector, discount rates of 7 or 7.5% are more common, because, I guess, the politicians know they won’t be around to deal with the blow back when the impact of the underfunding hits (as is starting to happen now). Unless “This time is different,” the business cycle suggests that the markets are not going to support those higher returns over the next decade or so. Honestly, I’m afraid 4.5% may prove to be too high.

Anyway, it’s good to see VF in touch with reality on this one.

CEO Rendle had this comment about how VF was becoming more “retail centric.”

“…you’re seeing greater attention to thinking and acting like a retailer, focusing on sell-through and getting our very best products on the floor at the beginning of the season, working dynamically to make sure those products are selling through and just keep the offer fresh, balanced with better and better marketing.”

I circled the term when I read the conference call and wrote “inevitable!” above it. It struck me that the need to become retail centric had started to appear perhaps 20 years ago, even if we didn’t identify it as such then. Basically, the requirement to address a customer who shopped a new way and had different priorities and sources of information made it necessary for brands to move in that direction and, finally, to become retailers. The ones who manage that well will be successful.