As pretty much everybody knows, Quiksilver filed for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy on September 9th. This is another step in a long process that’s been going on for years now and that we’ve followed together on these pages and in other places.

This will not be an explanation of bankruptcy or a discussion of why companies get into trouble. I’ve written those articles years ago (not specific to Quiksilver) and have posted them at the bottom of my home page under Classic Market Watch Columns. I sent that same link and information out last week. That’s probably the first time most of you have seen the bottom of my home page. Hell, I haven’t seen it in a while.

Before we get into some of the specifics of the filing and the plan, let’s briefly talk about what I think matters most.

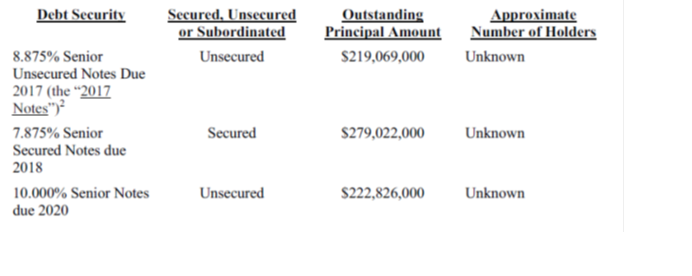

In every report from Quiksilver I’ve analyzed in recent years, I’ve asked, “Where’s the sales growth going to come from?” No amount of bankruptcy filing, restructuring, store closings, downsizing and rejection of contracts resolves that issue.

That doesn’t make the filing unimportant. As I wrote before the filing, some form of restructuring had to happen because the existing balance sheet and implied cash flow did not support continued operations. As a result of the filing, and assuming the plan is approved, debt and interest expense will decline and so will other expenses. For example, Quiksilver reported it had north of 700 stores at April 30. Lease contracts for unprofitable stores will be rejected in bankruptcy and the store count will decline. That will reduce expenses further.

But it will also reduce sales once the liquidation of excess inventory that results from the closings is done. I’m fine with that. The Quiksilver, Roxy and DC brands could all stand to be a little less broadly distributed from a brand building point of view. As you know, however, I believe there’s a potential conflict between building brands with hard to differentiate products and being a public company.

My point is that none of this restructuring stuff matters unless consumers want to buy products with the Quiksilver, Roxy and DC names on them. The good news in that regard is that consumers typically don’t notice a bankruptcy filing. With that in the back of our minds, let’s look at what’s happened.

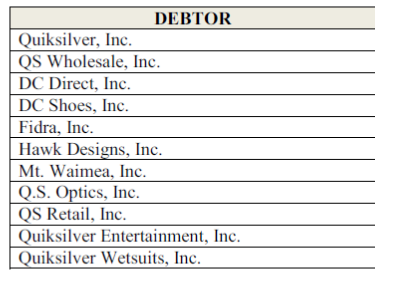

Who Filed for Bankruptcy?

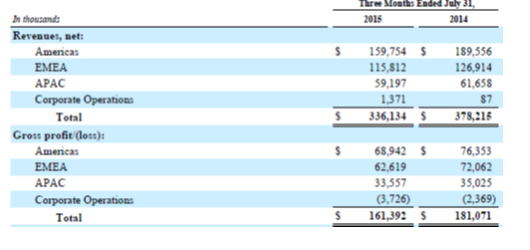

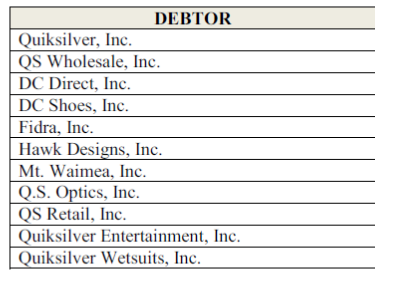

While it’s easy to say, “Quiksilver filed for bankruptcy,” that’s not an description adequate for our discussion. Quik’s U.S. operations filed. Here’s a list of the legal entities included in the filing.

And here’s Quik’s complete organizational structure from one of the filing documents. I know the picture is too small to really read, but I just wanted you to have a sense of the scope of the legal entities composing what we think of as Quiksilver. The shaded boxes are the ones filing for bankruptcy, and correspond to the list above. The legend at the bottom right of the chart refers to the shaded boxes as “Non-Debtor.” I think that’s a mistake.

Now, why do you care?

A “Prepackaged” Filing and the Role of Secured Creditors

Without getting into too much detail (like I’m going to be able to avoid that), you are probably aware that Quik has various pieces of long term debt. Around one-third of it is secured. That is, if Quik doesn’t perform under the terms of the deal under which they borrowed the money, the secured debtholders can seize the collateral securing the loans. Collateral can include various classes of assets including inventory, receivables, cash, trademarks, buildings, etc. It just depends what’s in the agreement.

That doesn’t change in bankruptcy. The secure creditors still have the right to the assets if Quik doesn’t perform under the loan agreement. But if the secured creditors take their collateral, Quik ends up selling its assets for the benefit of its creditors, the company goes away, and the secured creditors get less than if they can somehow restructure the debt and keep Quik operating. Or at least so they’ve apparently calculated. Knowing what I know about what happens to asset values in liquidation scenarios, I suspect they are right.

So a secured creditor has some leverage, and you can’t do a chapter 11 bankruptcy, prepackaged or otherwise, without their cooperation. Quik has played “Let’s Make a Deal” with that creditor in advance, and the plan is effectively part of the filing.

The press release tells us the filing “…is supported by 73% of the Company’s senior most class of debt…” It further tells us that “…holders of the Company’s Eurobonds sufficient to waive any technical default arising from the filing have agreed to allow the Company to reorganize its U.S. operations in Chapter 11.”

The rights and remedies of the secured creditors are no doubt carefully spelled out in documents, and you may all feel free to go find and read those documents to your heart’s content, because I’m not going to. My hope is that whichever, if any, secured creditors may not have agreed to this deal don’t have the ability to slow it down. The whole purpose of a prepackaged deal is to get the company in and out of bankruptcy quickly.

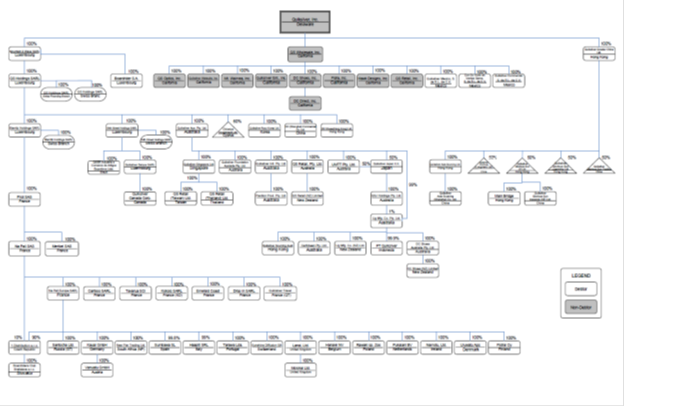

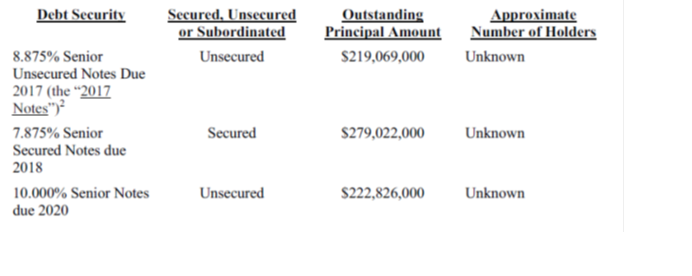

Here’s a list of the three biggest chunk of Quik’s debt included in the filing. The first one is the notes denominated in Euros.

You’ll note the $279 million in secured notes in the middle. You may also notice that none of this is due to be repaid farther away than 2020, and the first notes (the ones denominated in Euros) are due in 2017.

Who’s Getting Treated How and Just What’s the Deal?

The thirty largest unsecured creditors are listed in the original filing. The biggest by far is US Bank as trustee for $225 million of unsecured notes. That’s the third item on the chart above. The next largest is, I think, a supplier and it’s for $7.3 million. Most of the rest are for merchandise, but there is a couple for “real estate” that I take to be store leases. Don’t know for sure. There are a few individuals for severance. As you are aware, Quik already stop paying under its severance agreements (35 people I think), but most of those amounts aren’t big enough to make the top 30. The smallest amount on this list is $931,000.

Unsecured creditors don’t typically do well in a chapter 11 filing, but in this case it sounds like some will do better than others. What I’ve typically seen is that they have to be dealt as a single class and treated equally. They can’t be paid until the case is settled, though they can continue to sell to the filing company (in this case Quik) if they want to.

Quik, however, has petitioned the court to pay some or all of what they owe to “critical suppliers.” The court has approved those payments up to some specific limits. That makes some sense to me because they need these suppliers to get product. If these suppliers start messing with production or the supply chain, Quik could be in a world of hurt quickly. Okay, they already are, but even more hurt.

I wonder- if I were one of those critical suppliers, I’d be thrilled to get paid but I’m not clear how excited I’d be to continue to give Quik terms on new products. Those must be interesting discussions.

It would be great if some lawyer reading this would explain what I don’t understand. I know bankruptcy judges have a lot of discretion (they should), but I’m surprised you can treat some unsecured creditors differently from others.

The rest of the unsecured creditors are not going to do quite so well as the critical suppliers. They would “…receive cash in an amount equal to its pro rata share of the Unsecured Creditor Recovery.” The total of that Unsecured Creditor Recovery is $7.5 million. We haven’t yet seen the schedule that shows us all the unsecured creditors, but I’m thinking this will mean pennies on the dollar.

Then there are the holders of the common stock. There’s a 60 page list of those people. Interestingly, there seem to be an awful lot of people who own one share. Last time I saw, Quik stock was trading between $0.08 and $0.10 a share. As currently structured, those shareholders are going to end up holding common stock that’s worth exactly and specifically zero. Just to be clear, here’s how Quik put it in an SEC filing. “All of the Company’s existing equity securities, including its shares of common stock and warrants, will be cancelled and extinguished, without holders receiving any distribution.”

Like the people with severance agreements, some store landlords can expect their leases to be rejected in bankruptcy. Quik will close the stores where they choose to do that, though they would have the option of renegotiating the leases with the landlord to get more favorable terms.

So far, there are 27 stores to be closed and, in fact, that process started before the filing when Quik made a deal with a liquidator to sell the inventory and fixtures in those stores. The process is to be completed by the end of December.

Quik has also opened some “pop up” locations to dispose of obsolete or distressed inventory. I don’t quite know if that refers only to the inventory from the stores being closed or not.

Product from all three brands is involved in the store closing and liquidation. This can’t be good for the brand’s market perception.

The happiest people in this deal have to be the ones who hold the Euro notes. Basically, if they keep quiet and don’t cause trouble, the non-debtor foreign subsidiaries will continue to pay principal and interest as it comes due during bankruptcy, and the claims of the Euro holders will be unchanged when Quik exits bankruptcy. And if they want, they can get 25% of their notes paid down if they agree to extend the maturity by three years. Quik would like those notes not to have to be paid in 2017.

The other two sets of notes, totaling about $500 million, will go away. That will result in a big improvement in the balance sheet and reduction in interest expense. However, the 2018 notes can be converted into common stock. The 2020 notes will be in the unsecured creditor pile and get not much as I described above. Boy, are they screwed.

Oaktree Capital, as you know, will provide part of the “debtor in possession” (DIP) financing. Some lenders like to do DIP financing because it has a priority in bankruptcy over just about everything. As I recall, it’s senior to all claims except taxing authorities and the professionals (lawyers, accountants, etc.) who work on the case. Oaktree will provide $115 million in DIP financing. Bank of America will provide another $60 million, essentially continuing their asset based lending facility through the bankruptcy process.

By definition, asset based lending facilities are secured. But you don’t see it in the debt list above because it’s short term borrowing. There was $33 million outstanding under that line at April 30. I’m guessing that maybe there was $60 million outstanding at the time of the filing.

When they exit bankruptcy, Bank of America will replace its existing ABL line with a new $75 million line. As a secured creditor, it appears they will more or less come out of this whole. Asset based lenders usually do.

“Upon consummation of the Proposed Restructuring, the new Company will be funded by two separate rights offerings of up to $122.5 million and €50.0 million, respectively. Both rights offerings will be backstopped by the Plan Sponsor [Oaktree]. It’s the owners of the $279 million of notes due in 2018 and of the Euro notes that will have the chance to participate in these offerings. And if they don’t participate, Oaktree will take the whole amount. That’s what’s meant by “backstop.”

This will apparently involve some combination of new debt and common stock at a discount price. We don’t’ yet know what the new price will be. The proceeds from those two offerings will be used to repay Oaktree it’s DIP financing (yes, they may end up partly repaying themselves), paying the unsecured creditors, buying back the 25% of the holders of the Euro debt from those who want to extent their notes for three years, and for “general corporate purposes.”

What Does This All Mean?

As I started off telling you, no amount of restructuring addresses in any way the attractiveness, or lack of attractiveness, of Quiksilver’s brands in the market. But, hopefully, it gives them another chance to focus on that.

That was the whole idea when they got out from under the Rossignol debacle and brought in financing from Rhone, but here we are with a bankruptcy filing. In the words of Quik CEO Pierre Agnes in the press release, “Our fresh capital structure, with a very low level of debt for our industry, will enable us to invest in and reinvigorate our brands and products. We are confident we will emerge a stronger business, better positioned to grow and prosper into the future.”

This restructuring does a lot more for the balance sheet than the prior one. But I bet if I went back and looked at the press release for that deal, I’d find similar words.

The next thing I’m focused on is the roll of Oaktree. As you know, they are a major investor in Billabong, and now in Quiksilver. All over the summary plan document is the recurring phrase, “…which shall be in form and substance acceptable to Oaktree.” How is this going to work exactly? How much control will Oaktree exert? Their representatives resigned from the Billabong board right before the filing, but I’d be pretty surprised if somewhere, somehow, Oaktree people hadn’t thought about some kind of coordinated strategy or consolidation or sharing of functions or something. I doubt the legal and ownership structure would permit that right now, but everybody wants to be the next VF.

Quiksilver stock, as you probably know, has been delisted from the New York Stock Exchange. As of September 10th, it was traded on the over the counter market under the symbol ZQKSQ. Large chunks of stock are going to be owned by Oaktree and others. Someday, it’s possible they may want that stock to go up in value so they can sell it and make money.

I’m guessing that if things go well for Quik, we’ll see a secondary offering a year or three down the road so that the current shareholders can have some liquidity for their holdings. But we don’t have to worry about that right now.

Meanwhile, somebody sent me a copy of a letter than Quiksilver President Greg Healy sent out to dealers more or less when the filing occurred. I’m not going to reproduce the whole letter, but I want to quote one sentence.

“The challenges we face today stem from poor decisions made by previous management, which saddled the Company with a burdensome debt load.”

I’m kind of wondering what they mean by “previous management.” Not Andy Mooney. The debt was there before anybody at Quik had ever heard his name. It’s true that Andy didn’t understand the market, but he was also responsible for initiating a bunch of operational changes that should have been implemented, in some cases, years sooner.

This statement really bothers me, because it suggests not being completely in touch with reality. There is nothing worse in a turnaround. And the longer a turnaround lasts, the more the pressure builds and the harder it gets to be in touch with reality. Andy Mooney may have been the wrong outsider, but my experience is that an outsider is a good idea. I am wondering just how much leverage Oaktree will exercise in this area. Remember, they brought Neil Fiske into Billabong.

I’m going to urge you all again to go to the bottom of my home page under Classic Market Watch Columns, and read the one about why companies get in trouble.

The next court hearing is scheduled for October 6th. I’ll watch for new documents and try to keep you up to date. In the meantime, keep in mind that this necessary step doesn’t solve all Quiksilver’s problems- it just gives them another chance to address them.