In Touch with Reality? Big 5 Sporting Goods Quarter

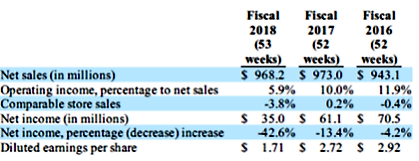

For its September 30 quarter, 436 store Big 5 reported a small decline in revenue and a larger decline in net income. More significant to me are comments in the conference call that suggest a very traditional retail focus, rather than one acknowledging the massive changes required to succeed at retail.

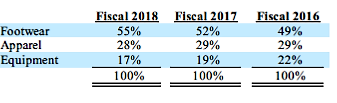

Revenue in the quarter fell 1.5% from $270.5 million in last year’s quarter to $266.4 million in this year’s. 54.8% of the quarter’s revenue was from hard goods. Apparel was 16.9% and footwear 27.8%. A 2% decline in comparable store sales was the major reason for the revenue decline. I want to highlight the following comment from the 10-Q as part of the revenue discussion:

“Sales from e-commerce in the third quarter of fiscal 2018 and 2017 were not material and had an insignificant effect on the percentage change in same store sales for the periods reported.” You might also want to look at their web site.

It’s 2018 and a 436-store retailer has e-commerce revenues that are “not material?” Hmmmm. Wonder how much e-commerce related expense it takes to produce “not material” revenues.

The gross margin fell from 32.4% to $31.0%. Revenue reduction was the biggest cause of the decline. Second was higher distribution expense of 0.73% including increases freight costs. Lot of that going on. Store occupancy costs accounted for 0.42% “…due primarily to lease renewals for existing stores.”

Finally, there was 0.10 decline in merchandise margins.

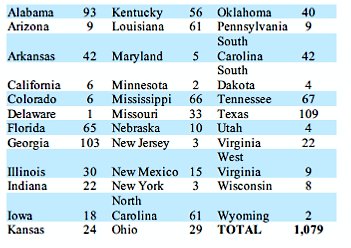

SG&A expense rose a couple of hundred thousand to $77.7 million. As a percent of revenue, they rose from 28.6% in last year’s quarter to 29.2% in this year’s. Minimum wage increases, especially in California where more than half of their stores are located, caused a $400,000 increase with more coming.

Operating income was down 52.7% from $10.2 to $4.8 million.

Interest expense rose from $447,000 to $860,000 reflecting both higher debt levels and an interest rate that rose 1%. That’s happening to many companies.

Income taxes fell from $3.79 million to $844,000 “…primarily reflecting a reduction in the federal corporate income tax rate…” The decline in net income was 47.7% from $5.95 million in last year’s quarter to $3.12 million in this year. Consider how much more net income would have fallen if not for the reduced income taxes.

Net cash used in operations for the six months ended September 30 was $8.06 million, up from $5.55 million in the same six months last year. You’d rather see cash generated by operations rather than used.

On the balance sheet cash, at $5 million is down about $300,000 from a year ago. Inventory has risen from $309.3 to $314.8 million. They note they are carrying over some inventory to next year- a common practice these days (but also indicative of a lack of product differentiation in the industry). The current ratio has improved from 2.07 to 2.36 times. Long term debt is up from $46.4 million a year ago to $83.5 million at the end of this year’s quarter. Equity has fallen by 11.3% from $203 to $181 million.

The quarterly dividend has been reduced from $0.15 to $0.05, reflecting the weaker financial position and operating results.

Let’s move to the conference call. On the positive side, Chairman, President and CEO Steve Miller says, “With our new POS system now in place, we are expanding our customer relationship management capabilities, which should provide enhanced customer analytics and improve the effectiveness of our marketing efforts.”

Collecting, slicing and dicing, and making better use of customer data is something every retailer has to be figuring out how to do better. They also are increasing their digital advertising spend at the expense of newspaper advertising.

But other comments seem traditional. There’s a generic statement about the change happening in retail, but what I hear in their comments is a tactical urgency to deal with the current financial situation (not inappropriate) rather than a strategic acknowledgement that a lot has to change- quickly.

“We are testing pricing strategies to be more responsive to an increasingly promotional competitive retail environment.” He mentions that again in part of his response to an analyst’s question.

Well, okay, but if you’re planning to compete on price with brands lots of others carry with your current real estate model in an environment of over supply and limited product differentiation, you might have a hard time. No brick and mortar pricing strategy is likely to win in an online world unless the product offerings are distinctive in ways that probably have to go beyond the actual product attributes.

“From a product standpoint, we are accelerating the pace of change within our assortment. This includes downsizing certain product categories to position us to be more aggressive in pursuing product opportunities that we believe have higher growth potential.”

Again, fine, but tactical. Have you acknowledged the fact that brands are going to turn over faster? How are you identifying and bringing in new brands and what’s the process for getting them in the right stores? How’s the micro sorting going?

There are a couple of mentions of finding new ways to reduce expenses. That’s great, but of course there’s a limit to it and as they describe it, it sounds tactical. Successful retailers won’t be the ones that reduce expenses; they will be the ones that increase expenses in a way that improves margins, provides a better customer experience, and ties brick and mortar and online together in a way that ultimately reduces costs.

It’s hard to know too much about what’s going on from what they say in a conference call, but I work with what they give me. I suggest you visit a Big 5 store then perhaps a Dicks and see what you think. I’d like to see more sense of urgency from Big 5. An acknowledgement of the interdependence of brick and mortar and online as a means of providing customers with the flexibility and connection they require would make me feel a whole lot better too.